Kenya Declared Free of Sleeping Sickness by WHO

Kenya Becomes the 10th African Nation to Eliminate the Deadly Disease

The World Health Organization (WHO) has officially declared Kenya free of sleeping sickness, confirming the disease is eliminated and no longer a public health problem in the country.

Sleeping sickness, or human African trypanosomiasis (HAT), is a parasitic infection spread to people through the bite of the tsetse fly. For over a century, it posed a deadly threat to rural communities across Africa. Kenya’s success makes it the 10th country on the continent to reach this milestone, joining nations such as Ghana, Uganda, and Côte d’Ivoire.

After a person is bitten by an infected tsetse fly, the parasite, Trypanosoma brucei. multiplies in the blood and lymphatic system. Without treatment, the infection can advance to the brain and affect the central nervous system.

The disease earned its name from one of its most visible symptoms—severe disruption of sleep patterns. Other signs include fever, confusion, poor coordination, mood changes, and sensory problems. Without treatment, the disease is almost always fatal.

In the 1990s, sleeping sickness was still a major public health crisis in Africa, with around 40,000 new cases reported each year. Health experts believe the true number was much higher, as many rural communities lacked access to diagnosis or treatment. Since then, international health campaigns, new medicines, and stronger surveillance systems have dramatically reduced its spread.

Since 2018, the total number of reported cases across the African continent has stayed below 1,000 per year, showing how far the region has come in tackling the disease.

Kenya’s Path to Elimination

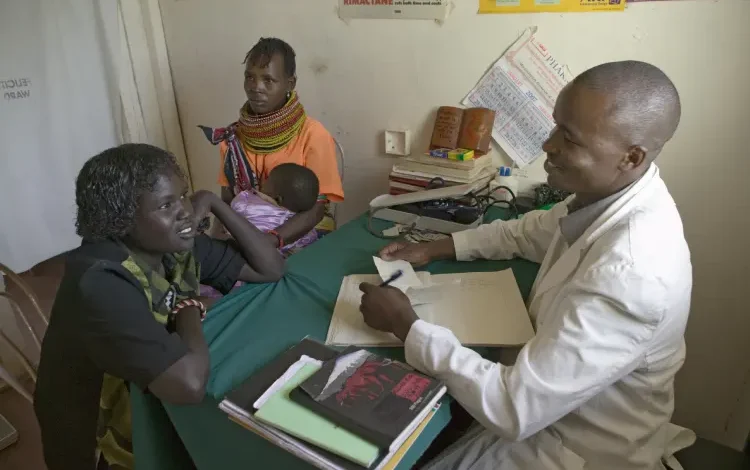

The earliest known cases of sleeping sickness in Kenya were documented in the early 20th century. For many years, the illness mainly affected rural communities, especially those dependent on farming, herding, hunting, or fishing—livelihoods that increased contact with tsetse flies.

The country recorded its last locally transmitted case in 2009, while imported cases linked to tourism in the Masai Mara Reserve were detected in 2012. Since then, no new human cases have been confirmed.

Kenya’s elimination strategy involved:

Stronger surveillance: Health authorities set up 12 health facilities in historically affected counties, trained medical staff, and equipped them with improved diagnostic tools.

Animal and insect monitoring: Veterinary services and the Kenya Tsetse and Trypanosomiasis Eradication Council (KENTTEC) worked to track parasites in animals and control tsetse fly populations.

Global partnerships: WHO and partners such as FIND, Sanofi, and Bayer supported Kenya with medicine stockpiles, technical expertise, and research collaborations.

The Road Ahead

Although elimination is a major step, it does not mean the disease is completely gone. Kenya will now continue post-elimination surveillance. Health facilities will keep screening for the disease, particularly in regions where tsetse flies are found, and WHO will maintain supplies of medicines in case new cases appear.

Kenya is now the second country after Rwanda to eliminate the rhodesiense form of sleeping sickness, which progresses faster than the gambiense form found in West Africa. Experts say this shows that sustained investment and community-based health programs can deliver lasting results.

The WHO aims to wipe out sleeping sickness as a public health concern across Africa by the year 2030. With ten countries, including Kenya, already validated, health officials are optimistic that this target can be achieved.

Globally, 57 countries have now eliminated at least one neglected tropical disease, a sign that coordinated international action can defeat illnesses that were once seen as unstoppable.

[Source]